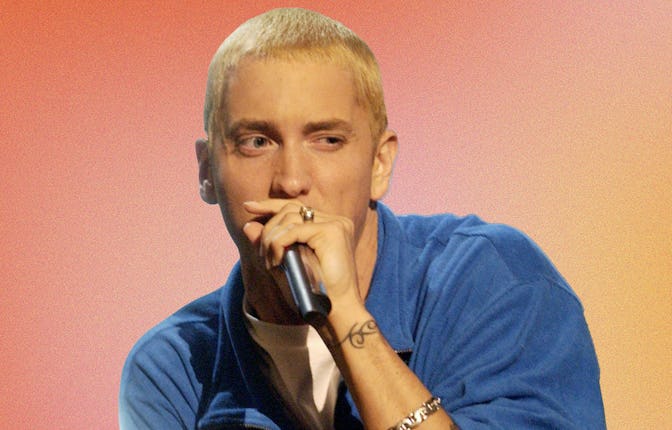

On The Eminem Show, the rapper sharply skewered society — but lost sight of himself

The album that closed the first stage of Eminem’s career was fueled by his steadily fraying personal life.

It was probably inevitable, from the moment the first letters were mailed and federal agents swarmed East coast post offices in hazmat suits, that Eminem was going to rhyme “anthrax” with “Tampax.” The Detroit-bred rapper had become a superstar at the tail end of the Clinton years —allegedly boom times, when his provocation for provocation’s sake was enough to disturb a middle-American calm — and any news event that paralyzed the public at large was sure to animate him. But plenty had changed between his second album, the staggeringly huge The Marshall Mathers LP, and his third. There was the Bush-Gore election and subsequent Supreme Court battle; the September 11th attacks and those anthrax shipments; the invasion of Afghanistan and the saber-rattling in Iraq. The mood of the country was totally transformed. (Later anthropologists might call this a “vibe shift.”) The pop-cultural landscape he surveilled from its top was not the same one he clawed into on his ascent.

While this political and psychological realignment was taking place, the artist’s personal life was fraying. Where Eminem had once taken evident joy in skewering the flourishing tabloid culture and the celebrities who were locked in symbiotic step with it, he now found himself at its center. On one day in the summer of 2000, he brandished a gun two times: during an altercation with the Insane Clown Posse and later, outside of a bar where he claims to have seen his wife, Kim, kissing a bouncer, and is alleged to have pistol-whipped him. (He would plead out in the pistol-whipping case and receive probation.) About a month later — just days after a Detroit concert where Eminem performed “Kim,” a song that imagines her murder, while choking a blowup doll of her likeness — Kim attempted suicide. She would go on to sue him for defamation, a suit which could be added to ones from his mother and a former classmate who felt he was slandered in yet another song. All of this was covered exhaustively.

The maxim says that you have a lifetime to write your first album and six months to write your second. Yet while Interscope had surely wanted The Marshall Mathers LP out soon after The Slim Shady LP proved itself a phenomenon, Eminem was allowed to spend some time away from the din — so much so that he almost named that record Amsterdam, after the city he hid out in while he wrote many of its tantalizingly elastic verses and plotted his way through the gummy basslines and yawning negative space in the beats that Dr. Dre and Mel-Man played him over transatlantic phone calls. It was the third LP that was recorded haphazardly — in between takes for 8 Mile, the quasi-autobiographical film that would be released the same year, so fast that Dre did not seem to have the same talking points about it as the headliner. Inspired by the Jim Carrey movie, the rapper gave his sloppily agitated album about life in the spotlight the only name that would fit: The Eminem Show.

The Eminem Show is not exactly a portrait of a man on the brink. There are startling confessions — some designed as such and some unwitting — but the album begins and ends in total control. And still, there is an unraveling of sorts that happens here: the personal from the political, the persona from the man behind it. This deconstruction is less revealing, or at least less rewarding, than it sounds. The magic trick Eminem pulled on The Marshall Mathers LP — other than that album’s musical ingenuity — was the total coalescence, in nearly every verse, of all his concerns as an artist, with the wrenching autobiography, the free-speech absolutism, and cartoon violence coiling around one another until they became inextricable. When those threads are isolated from one another, some are shown to be radically more compelling than the others.

For how thoroughly some pieces of Eminem’s life had been subsumed into his myth — his tumultuous relationships with Kim and his mother, the tender one with his daughter, Hailie — it can be easy to forget the way the pistol-whipping incident looms over The Eminem Show. It’s not only recreated on one of the album’s skits, but used as the organizing event for “Soldier” and “Say Goodbye Hollywood” and for the emotional climaxes in “Sing For The Moment” and “Cleaning Out My Closet.” But it, like the other introspective notes The Eminem Show strikes, is rendered with too little ironic distance and too much self-pity. This is an aesthetic gripe, to be sure; we’re talking about a parent who was facing prison time. But it’s hard to take seriously an artist who has needled the wealthy and comfortable at every step of his career when he raps about being a “soldier” — and stops just short of comparing himself to 2Pac — for waiting in a bar parking lot to catch his wife cheating on him. The tonal setup is so clumsy that it relinquishes any plausible claim of unreliable narration, here and elsewhere: When he raps, on “Hailie’s Song,” “I’m so glad her mom didn’t want her,” he seems cruel for putting that notion in the world, not fascinatingly complicated like he must have hoped.

While The Eminem Show is certainly a major work, it does not play like an album that was given the necessary time and attention to cohere into what it could have been.

The album is far more effective when Eminem turns his gaze outward — especially toward the new administration. The Eminem Show was released (a week before its scheduled date, to combat rampant bootlegging) less than nine months after 9/11, at a time when George W. Bush’s approval rating was hovering in the high 70s and radio stations were blacklisting artists who dared speak out against America’s Middle East incursions or domestic spying apparatus. But Eminem prodded. From “Square Dance”:

“‘All this terror, America demands action!’

Next thing you know, you've got Uncle Sam's ass asking

To join the Army, or what you'll do for their Navy

You just a baby getting recruited at 18

You're on a plane now, eating they food and their baked beans

I'm 28 — they gon' take you 'fore they take me!”

To mock those who eagerly enlisted in late 2001 and early 2002 is to go as brashly against the cultural grain as possible; later on the album, in what at first seems like a throwaway line, he raps that there’s “no tower too high/no plane that I can’t learn how to fly.” The rejections of the so-called war on terror were intriguing on their own, but also gave new gravity to his squabbles with the FCC (“Without Me”) and spats with cultural conservatives over his lyrics. And suddenly, all that sand-shifting around him turned his position into the one of obvious moral righteousness: The puritanism he found merely annoying during the Clinton years was being leveraged for something acutely horrifying. Imagine Woody Guthrie rapping in a Robin costume with a giant prosthetic bulge.

Eminem continued to rap, as he had on prior albums, astutely and with some humility about the role race played in his career. The Eminem Show opens with “White America,” whose hook is one of the most viciously taunting passages in his catalog (“I could be one of your kids… I go to TRL, look how many hugs I get!”). He underlines the obvious (“Let’s do the math: If I was Black, I would’ve sold half”), but also gives an oddly even-handed assessment of the persona that made him famous: “So much anger aimed in no particular direction/Just sprays and sprays.” This gives him the latitude to draw the line he does on “Without Me,” where he compares himself to Elvis Presley for profiting off a Black art form — but then mocks the lemmingish record executives who were trying and failing to replicate his success with white rappers of their own.

Yet even most of those songs are dragged down by production that is pedestrian at best. There was a point during the MMLP sessions — and this has been well documented, speaking of the story being swallowed by the legend — after Dre and Eminem had believed the album done, but Interscope requested he return to the studio in search of a lead single. He found one, in “The Real Slim Shady,” but also recorded “The Way I Am,” a static screed over a morose piano loop. It, too, became a hit — and was the first time Eminem was credited as a primary producer. That song, beloved by many fans, was a terrible omen for Eminem’s later work. Where he was once an infinitely pliable rapper, his verses skipping and stuttering around the beat, “The Way I Am” made him comfortable in a drone, his intensity cranked all the way up and then stuck in that gear.

This would become a far more serious problem in the 2010s, but creeps into the vocals on songs like “Soldier,” “Closet,” and “Sing For the Moment.” (While the volume is turned down, even lighter records like “Business” find him stuck in an apathetic rut.) More frustrating is the “Way I Am” hangover on the production side. Eminem was simply not ready to handle a major rap album’s beats, as he does for almost the entirety of The Eminem Show, which on the whole sounds tinny and rhythmically flat, its biggest swing a mawkish Aerosmith flip. The beats would be a disaster if given to another artist; Eminem had a thorough enough understanding of his needs as a hyper-technical rapper that he frequently finds smart pockets and occasionally, as on “Without Me,” strikes on a wonderfully playful tone. But there is none of the whiplash verb that marked the best songs on his previous LPs.

While The Eminem Show is certainly a major work — in some ways the last of his career’s first phase, as 2004’s Encore was hampered by his struggles with substance addiction — it does not play like an album that was given the necessary time and attention to cohere into what it could have been. (This is evidenced even by the songs picked for an expanded edition, released to streaming platforms this month: Only one of the bonus tracks is from this era, with the others dating to a mixtape run from the following year, when he had moved into a new creative phase, or from the MMLP sessions.) What stays with you is the desperation. For all the tonal incongruity and musical flatness that runs through the LP, there is a white-hot hunger at its center. Take “Till I Collapse,” a song that has become a gym-playlist staple despite being a slightly paranoid stock-taking of Eminem’s career at that moment. “Is it a miracle?” he asks in its first verse, “Or am I just a product of pop fizzing up?” The truth is that he was neither — he was, instead, a wildly talented MC with a keen eye for the social hypocrisy around him, whose own anger was threatening to swallow all of that from the inside.