The emotional rollercoaster of passing as cis-het

I do sometimes enjoy the perks of cis-het privilege, but I don’t actually want to pay the price of passing for straight or female.

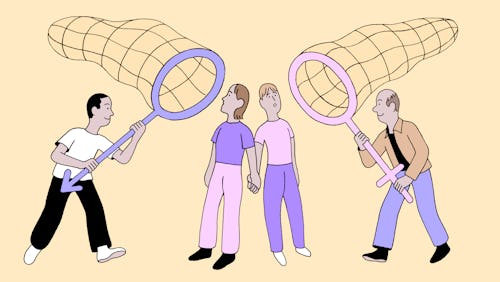

I recently went on vacation to Puerto Rico with my partner, who is a person who was assigned male at birth (AMAB). I'm nonbinary, but solidly femme, so to anyone stubbornly existing in the cis-heteropatriarchal matrix, we look like your average white m/f couple. Generally speaking, this kind of “passing” makes everyday life a lot less stressful. When people see me holding hands with a (presumably straight, since that’s the norm in our society) AMAB person, I am instantly granted all the perks of het coupledom — men don’t hit on me and women don’t assume I'm hitting on them — and best of all, no one stares in rapt normcore curiosity trying to parse out our genitalia or sexual preferences. It’s amazing.

The problem starts when I have to start explaining my pronouns or, worse, when people assume that my partner is in charge of me or somehow authorized to speak on my behalf. “And for her?” is a question always directed at him, which never fails to make me throw up a little in my mouth. The bizarrely unshakeable construct that men are in charge of women in cis-het couples is bad enough, but queerness and gender non-conformity adds even more complexity. In a flash, I go from feeling comfortably unnoticed to being simultaneously invisible and also an anomaly.

Like, yes, of course, I do enjoy some of the perks of cis-het privilege — like having strangers coo about what a cute couple we are and not being bullied in bathrooms — but I don’t actually want to pay the price of passing for straight or female. It makes me feel a burdensome responsibility when I am forced to insist on the validity and the reality of my existence. And because defenders of the patriarchy almost never enjoy being confronted with their waning hegemony, it’s also a pretty quick vibe killer in most any situation.

On a beautiful day in paradise, we hired a guide to take us snorkeling in the coral reef. On the way to meet the dive guide, my head was full of neon fish and sea turtles. “Good morning ladies and gentlemen,” the guide in blue swim trunks said when he greeted us. I cringed. “Oh, I know gender is complicated these days,” the man said, gesturing at me, “but I believe a lady is a lady.” “We do not agree,” my partner said, squeezing my hand. I was already starting to dissociate.

For three hours, the man in blue trunks would not meet my gaze. “Kishon,” he would say, looking at my partner, “what size does she wear?” “They,” I said. “Kishon, can you grab her fins?” he persisted. “They,” I said flatly. The hungover Australians on the excursion somehow made everything seem worse, even though all they really talked about was artisanal rum. They were girls who looked and acted like girls, smiling and nodding when they should while I flipped my sunglasses down and made my mouth into a straight line. Internally, I was freaking out, but I felt like if I pushed my feelings aside and kept my mouth shut, at least I wouldn’t start a scene and make everything worse.

The dive, which had promised to be a magical undersea adventure, was tainted by tension. Don’t get me wrong, seeing a baby sea turtle was truly extraordinary, but interpersonal drama cast a shadow over everything. The guide said he was frustrated by the clouds in the sky and what he seemed to take as me and my boo’s seeming inability to lighten up. We chafed against each other in the close quarters of the van and in the vast expanse of the Caribbean Sea. The man got increasingly more agitated.

He went on a tirade about “the state of Puerto Rico.” The Spanish weren’t actually the cruelest colonizers of Puerto Rico, according to blue shorts, it was the Mayans and if people would stop blaming the U.S. and get off welfare, the island would undoubtedly prosper. I found it hard not to gape at his insular conservative views. It did make sense to me, though, that someone who was so attached to the gender binary was also a colonial apologist.

The sea and its inhabitants were breathtaking, but I don’t think anyone on the dive, save perhaps the boisterous Aussies, could fully enjoy their aquatic splendor. Our versions of reality could not be reconciled and the dissonance was really fucking with all of us. The guide could not comprehend that I was maybe not the girl he thought I should be and I could not tolerate the nauseating combination of his resistance to our gender fluid reality or his neurotic conservative mansplaining.

Eventually, he stopped she-ing me and I gave him an encouraging smile, but it was too late, and we all left feeling a little sad and confused. The truth about trying to deny reality is that it just persistently exists, and ignoring it takes a lot of energy. I am not a girl. My partner is not my “boyfriend.” We will not be rendered invisible even if it costs us privilege. We are queer and we are here and we’ve given everyone more than enough time to get used to it.