A Montana judge shut down a threat to Native people's voting access — for now

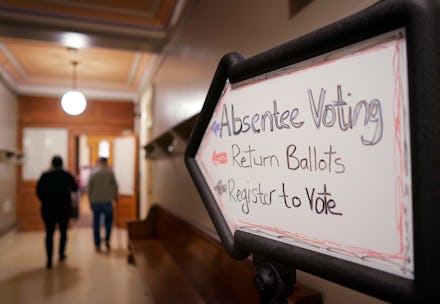

A Montana judge blocked a law this week that would have prevented Native Americans living on reservations in the state from casting their ballots in the primary election on June 2. The judge's ruling, called a temporary restraining order, halts the Ballot Interference Prevention Act, which limited the ability of organizers to collect completed ballots from voters and deliver them to election offices. Next week, the judge will hear arguments from both sides as to whether or not the law should be permanently overturned.

Earlier this month, a coalition of legal organizations, including the American Civil Liberties Union of Montana, filed a lawsuit on behalf of two indigenous-led get-out-the-vote organizations — Western Native Voice and Montana Native Vote — whose efforts relied on being able to organize vote-by-mail drives. On Native reservations, absentee ballot collection efforts led by community organizers are often the only way that Native voters can access the ballot box, as many live in very rural areas. In addition to requirements for state-issued identification, access to transportation can be a major roadblock for rural Native populations to deliver their ballots to the nearest polling location.

That's why the work of ballot collecting is so crucial for ensuring the franchise of these voters. "This is a good day for voting rights and civic engagement. While adhering to COVID guidelines to protect our communities and staff, our organizers can now continue their robust get-out-the-vote and ballot collection efforts on every reservation in Montana knowing that their important work will not be punished," Marci McLean, the executive director of Western Native Voice said in a press release.

An ACLU brief details the difficulties of accessing the vote on rural reservations. "Transportation is by no means a guarantee of accessibility. In Montana, blizzards can begin as early as the fall. During last election season much of the state was covered with up to 40 inches of snow. Nor have satellite polling locations been sufficient to provide equal access to the ballots."

The law is a "solution in search of a problem."

Collecting ballots from a number of voters during a vote-by-mail drive is an efficient and effective way to ensure that Native voices are heard on Election Day, proponents argue. In Montana, a state home to fewer than 700,000 residents, most voters cast absentee ballots during general elections, and absentee voting is the only way to participate in local elections.

In 2018, Montana voters passed the Ballot Interference Prevention Act, which included a provision that only six ballots could be collected and delivered to a polling location by someone who wasn't a poll worker or postal service employee. Lillian Alvernaz, the Indigenous Justice Legal Fellow at the ACLU of Montana, tells Mic that the law would have impacted every Montana voter, but disproportionately hurt Native voters. Alvernaz testified against the law's passage in 2017, and she says the law is a "solution in search of a problem."

Proponents of the BIPA, like Montana Secretary of State Cory Stapleton, said that the legislation would protect the vote by cutting down on supposed voter fraud. Republicans often refer to ballot collection with the nefarious-sounding phrase "ballot harvesting."

Problem is, some leaders in the Republican Party have acknowledged their own efforts to do so-called "ballot harvesting," and how crucial they believe the practice to be for their own success. California Rep. Devin Nunes, who has defended President Trump on a number of issues, said last week on Fox News the practice is the only way Republicans can win. "We don't like it, we don't want to, but we are forced to have to ballot harvest because it's the only way to win," he said, adding that "as long as we have a robust ballot-harvesting operation come November" a newly-elected Republican in California should be able to hold on to his seat.

There's little evidence to support the notion that get-out-the-vote ballot drives lead to illegal voting. In fact, research shows that expanding vote-by-mail opportunities benefits every voter, no matter their party. In past years, Montana has consistently voted for Republican candidates by large margins, so the presumed fear that voter access would lead to Democratic wins is largely unfounded.

In addition to stoking fears about voter fraud, legal experts also say that the attempt to disenfranchise Native voters is just the latest move in a history of voter suppression: "Even though the Indian Citizenship Act passed in 1924, Native people were still prohibited from voting in the 1950 election," Alvernaz says, noting that individual states issued laws that said Native voters had to pay taxes on their land or denounce their tribal citizenship if they wanted to cast a ballot. BIPA, Alvernaz says, is a continuation of Native disenfranchisement.

The judge's temporary restraining order, which prevents BIPA from taking place, will be argued in court on May 29. The state's primary is just four days later.