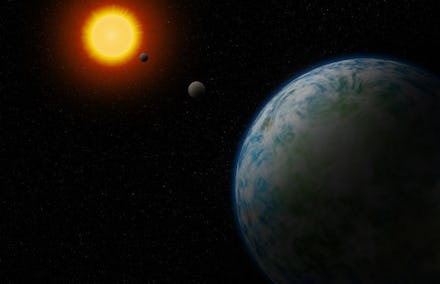

Scientists just found two more potentially inhabitable planets

Another day, another exoplanet discovery! At least, that's certainly what it feels like as of late, with astronomers successfully seeking out the celestial objects and stumbling upon some pretty impressive discoveries. Most recently, two new exoplanets that scientists are referring to as "Super-Earths" as well as a record-smashing "cold Neptune" were added to the veritable menagerie of space objects it feels like we've added to our galactic reach thus far. Is this the path forward to finally choosing a "replacement" Earth for the far-off future if (or when) Earth finally becomes uninhabitable?

It certainly feels that way sometimes, especially since the new "Super-Earth" exoplanets are possibly habitable. Orbiting red dwarf stars GJ229A and GJ180, these planets are about 19 lightyears and 39 lightyears from Earth, respectively. Red dwarf stars are similar to our sun in the solar system, but much smaller, and less bright. That means the habitable zones on the exoplanets, or the areas on the planet where liquid water could remain surface-stable, are closer to the stars they orbit around than they are with Earth and our solar system.

We've seen habitable zone red dwarf planets before, which was the case with the most recent discovery thanks to NASA's TESS finding the newly-christened exoplanet TOI 700 d. But TOI 700 d, like most similar exoplanets orbiting red dwarf planets are, is tidally locked. That means that the stars red dwarf planets orbit around only ever shows them the same side, much like Earth only sees one side of the moon.

It looks like that isn't the case with these new exoplanets, which actually happen to orbit far enough away from the red stars that they aren't forced into tidal locking. That alone makes GJ180 d, along with its partner exoplanet GJ229A c significant discoveries.

"GJ180 d is the nearest temperate super-Earth to us that is not tidally locked to its star, which probably boosts its likelihood of being able to host and sustain life," said Fabo Feng, Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington, D.C., team lead, in a statement.

GJ180 d is actually a bit bigger than Earth, with 7.5 times the mass of our planet. GJ229A c is also larger than the Earth, with about 7.9 times Earth's masses. But as the letters in the planets' names indicate, there are additional worlds in their systems as well. There's also GJ 433 d, which isn't quite a candidate for supporting life. It is, however, the "nearest, widest, and coldest Neptune-like planet" that's ever been detected, according to Feng. But while it's similar in size to the other planets, it's not really a good fit for people to actually live on.

Beyond those details, astronomers still don't know a lot about the new exoplanets, the so-called "Super-Earths." It may be a while, potentially when NASA's upcoming James Webb Space Telescope finally launches next year, before additional research becomes possible.

With the new telescope in the works for next year and continued study into exoplanets, their potential methods of supporting life, and all the other findings scientists are seemingly reporting every other week or so, it feels like we're painfully close to finding a planet that might actually act as a decent surrogate for humanity at one point far off in the future. There's still plenty left to explore, so that means we've hardly even scratched the surface when it comes to the possibilities the human race has kindly been afforded.