The federal government is about to execute the first Native man in nearly 100 years

Seventeen years ago, Lezmond C. Mitchell, an enrolled member of the Navajo Nation, was convicted on federal charges of murder and carjacking. Using a tricky legal maneuver, Mitchell was sentenced to death against the original wishes of his victim's family (though the family has since changed their perspective) and in contradiction with Navajo understandings of justice. Barring action from President Trump himself, Mitchell, now 38 and incarcerated at a federal prison in Indiana, will be executed Wednesday.

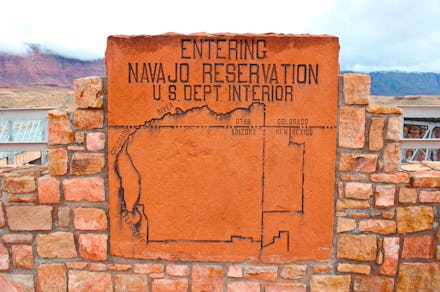

In 2001, Mitchell and a Navajo teenager named Johnny Orsinger, then 16 years old with prior convictions, were hitchhiking back to the reservation. The two hijacked the car of a 63-year-old Navajo woman named Alyce Slim, who was traveling back from New Mexico with her 9-year-old granddaughter. The men stabbed Slim and later killed her granddaughter, disposed of their bodies, and used the vehicle to rob a general store on the reservation a couple of days later.

In July 2019, Attorney General Bill Barr announced that the federal government would resume executions after nearly two decades of inaction. Now, Mitchell's lawyers are working to make one last attempt to keep him alive, as they've exhausted legal appeals through federal circuit courts. Mitchell received a stay of execution in 2019, but lost an appeal this summer to push back his execution date. Along with the Navajo Nation, his lawyers filed a petition for clemency through the Department of Justice. That means that Trump now has the final say as to whether Mitchell lives or is executed by the U.S. government.

On July 31, Jonathan Nez and Myron Lizer, the president and vice president respectively of the Navajo Nation, wrote Trump directly. "We do not know the details of the decision by the U.S. Department of Justice and the U.S. Attorney’s Office to seek the death penalty in Mr. Mitchell’s case," they wrote. "What we do know is the sovereignty of the Navajo Nation and our decision, while clearly explained, was marginalized."

Even though the crime took place on Native land against other Native people, federal agents were allowed jurisdiction to prosecute Mitchell and Orsinger because of a provision in the Indian Appropriations Act known as the Major Crimes Act. Because carjacking can be federally prosecuted under the Major Crimes Act, John Ashcroft, the attorney general at the time under President George W. Bush, was able to bring charges in federal court without deferring to tribal legal systems.

"In order for the federal government to pursue a death sentence against Lezmond, it had to rely on a legal loophole," Mitchell's legal team told Mic in an email. Mitchell legally couldn't be sentenced to death by the federal government for murder alone, but his legal team explained that he "could technically be sentenced to death for carjacking resulting in death because the federal government had jurisdiction to prosecute that charge as a capital offense regardless of where the crime took place."

Orsinger was handed a life sentence because he was minor at the time of the crime. Mitchell, convicted by a mostly-white jury, was sentenced to death. The decision contradicted what the families of Slim and her granddaughter wanted, as well as what the Navajo Nation wanted. Prior to Mitchell's sentencing, the attorney general for the Navajo Nation wrote to the local federal attorney arguing that the death penalty should not be pursued given the tribe's cultural, religious, and political opposition. Mitchell's lawyers told Mic that the letter was read to the jury, but "only 7 of the 12 jurors found the evidence to be mitigating."

Looking back on the trial, Mitchell's lawyers take issue with a number of factors: the fact that all but one person on the jury was white; that a judge moved the trial 100 miles from where Mitchell resided; that members of the jury were asked to sign a legal form attesting that they would not allow racist thinking to impact their vote; that lawyers weren't permitted to speak with members of the jury after the trial ended to see if there was any evidence of racism or prejudice, a practice that's allowed in most other trials. The list goes on.

"The arbitrariness of the death penalty in this case is apparent."

All of these factors are cited in the clemency petition that lawyers filed on behalf of Mitchell — along with the fact it was odd for the U.S. attorney general to seek the death sentence in the first place. In 2014, after lawyers appealed Mitchell's conviction (an appeal that was ultimately denied), federal judge Stephen Reinhardt wrote of the abnormal sentence: "The arbitrariness of the death penalty in this case is apparent," alluding to the fact that the prosecutors had to exploit a legal technicality to pursue the death penalty at all. "Mitchell raises a number of serious constitutional issues regarding both his conviction and his death sentence." The judge maintained that uncertainty remained "as to whether the judicial proceedings afforded Mitchell comported with the constitutional protections to which he is entitled. That uncertainty alone is sufficient to raise serious questions regarding whether Mitchell should be put to death by his government."

Prosecutors generally pursue the death penalty when the case is of national importance, as with Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, who was convicted for his role in the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing. But that wasn't the case with Mitchell, says Barbara Creel, a law professor at the University of New Mexico. Creel tells Mic that the pursuit of the death penalty in Mitchell's case was instead a patronizing and racist attempt to communicate that the U.S. federal government was "protecting Native Americans by killing Native Americans." Given that the Navajo Nation, which has a government-to-government relationship with the U.S., has objected to the death penalty, Creel says the only reason the federal government sought capital punishment was to further the colonial belief that "the only good Indian is a dead Indian."

In fact, the U.S. interpretation of Mitchell's case isn't really about justice, but power, Creel says. Centuries of federal and case law have outlined lesser protections for Native people, so much so that Creel says Native Americans are actually guaranteed different civil rights than non-Native people. "You can draw a direct line to that theory: that you need to civilize the Indians by killing the Native," she says. In other words, per Creel, the American conception of justice for Native Americans is to kill Native Americans.

The result is that tribal nations are prevented from exercising their legal right to autonomy and sovereignty in deciding what happens to their citizens, as in Mitchell's case. Overall, Native people suffer alarmingly high rates of violence, often at the hands of white people. That physical violence imposed onto Native people is supported and protected in U.S. legal doctrine that actually describe Native people in violent, degrading, and dehumanizing language like "savages, uncivilized, inferior race," says Creel. One example: The Declaration of Independence itself cites "merciless Indian Savages" as one reason for colonization.

"Where does the death penalty come from? Does it come from the Navajo Nation? No. Why does it apply to him? Because he is less than."

Had Navajo law been considered, or had Mitchell been permitted a trial within the Navajo Nation's jurisdiction, prosecutors would have likely pursued a penalty grounded in restorative justice — that is, consequences that are more about healing and less about punishment. By removing Mitchell from his home community, he was robbed of the opportunity to make amends, to heal with his people, and to learn from his past actions. Creel says that we need to put Mitchell's sentence in "context" of the history of the U.S.: "Where does the death penalty come from? Does it come from the Navajo Nation? No. Why does it apply to him? Because he is less than."

The imposition of federal law onto Native peoples despite existing treaties or agreements not to do so is not new. Alan Rogers, a professor of history at Boston College, explains that Indigenous peoples were sentenced to death for murder after King Philip's War in the late 17th century. After that, Rogers tells Mic, the signing of the Constitution supported colonizers' settlement of western states, and the newly formed Supreme Court reinforced the notion that land could be stolen, bought, and sold. The high court "gave license to settlers to take the land by hook or crook," Rogers says, referring to the fact that Native tribes didn't own their land and therefore didn't have deeds to soad land, which were the only forms of documentation that the U.S. deemed legitimate.

Then it was the development of a lower court system, after the creation of the Supreme Court, that allowed for federal law to govern what should happen with Native tribal land. White settlers "didn't have to slaughter people," Rogers says. "They could go to court and get access to the land."

The roots of U.S. federal law, born out of colonial systems, are essential to understanding contemporary judicial practice, says Robert Dunham, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center. "Just as the death penalty cannot be understood separate from America's legacy of slavery, lynching, and Jim Crow, Mr. Mitchell's punishment can't be understood outside of the context of the U.S. government's historical treatment of Native Americans."

In Mitchell's case, Dunham tells Mic, the family and tribe's "collective wishes were politically overwritten by John Ashcroft." And in restarting federal executions, Dunham argues that the Trump administration is "telling Native Americans that their views don't matter."

If Mitchell is in fact executed Wednesday, it will be the first federally-sanctioned killing of a Native person since 1938, Dunham says. An injunction has been filed in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia to allow for more time for Trump to consider clemency. But it's still entirely possible, if not likely, that Mitchell will be executed, against the wishes of the tribal nation he belongs to. "The United States has a shameful history with respect to its treatment of Native Americans and its continuing disrespect for the autonomy and integrity of Native nations," Dunham says. "I can't say whether this is an intentional act of disrespect, but it reflects everything that is bad about the federal government abusing its power in matters of Native sovereignty."