"It’s just got to stop": Columbus will close 2020 as the new center of the civil rights protests

After a summer of social unrest following the killings of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and other African-Americans at the hands of law enforcement, nationwide distrust of police officers swelled. Protests in Minneapolis and Louisville, where Floyd and Taylor were killed, respectively, overwhelmed the streets for days, and even in my hometown of Columbus, Ohio, tensions rose tremendously.

By winter, though, protests in Columbus had dissolved into a mere hum, down from their feverish intensity over the summer. That relative quiet lasted until the afternoon of Dec. 4, when 23-year old Casey Goodson Jr. was returning home from a dentist appointment with a Subway order in hand. On the doorstep of his northeast Columbus home, local Sheriff Deputy Jason Meade and two other officers in plainclothes encountered Goodson. Meade said later that he’d seen Goodson waving a gun around while he was driving a car, so he and the other officers pursued Goodson. An argument ensued, and as Goodson was attempting to enter his home, Meade shot him in the torso. Goodson’s keys were found in the doorknob, showing how close he was to escaping the confrontation.

Goodson was close to getting his commercial driver’s license; he wanted to become a truck driver and firearms instructor. He had a concealed carry permit and only had one minor offense on record: a traffic ticket.

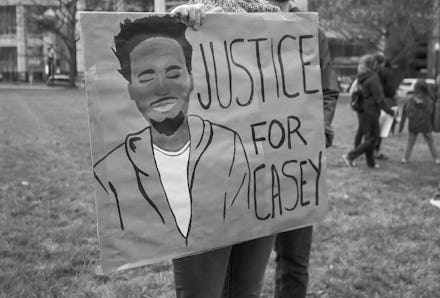

After Goodson’s death, Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine (R) imposed a statewide curfew, which will tentatively extend until Jan. 2, 2021. Though the Columbus Police Department seemingly hushed Black residents into submission this summer, with residents alleging they’d been targeted during the statewide curfew, that didn’t stop organizers from coming together in Goodson’s honor. On Dec 11, the weekend after Goodson’s death, thousands flocked to the Ohio statehouse in solidarity with Goodson’s family and in opposition to the local police. Goodson’s mother, Tamala Payne, called for peace alongside attorney Sean Walton Jr. and Goodson’s family members, who all wore matching hoodies printed with a cartoon likeness of Goodson.

The next day, Dec. 12, Chris Fannin, a protester who lived near Goodson's Estate Place neighborhood, spoke on the extensive history of police brutality in Columbus. “Police are trained to use their weapons, but if a gun hasn’t been pointed at their face [they] shouldn’t be shooting people. I’ve got a button from 1979 about the killing of a young Black man who was killed by a Columbus police officer in a car,” Fannin told me, referring to the shooting of Keith Burke, an unarmed 16-year-old who was shot in the back while fleeing white cops in plainclothes. Police alleged Burke attempted to run over an officer in a stolen cab. “That was 40 years ago, and here we are now. I was riding my bike on Casey’s street a month ago — a perfectly nice, quiet neighborhood. This could have happened anywhere to anyone, and it’s just got to stop.”

Meade had previously been reprimanded for deploying his Taser on a suspect without telling a supervisor about the excessive force, and he was placed on administrative leave alongside seven other deputies following a 2018 standoff. While Columbus Police Chief Tom Quinlin pledged that officers would wear body cameras and always have their badge numbers visible, residents have still reported instances where officers fail to abide by those rules. Consider the police killing of Andre Maurice Hill last week, where the officer in question didn’t activate his camera until after he shot Hill. (There is video of the encounter thanks to a retrospective recording feature on the camera, but the device doesn’t capture audio until it’s turned on.)

Conflict between Black residents and the Columbus police has steadily repeated itself in the last decade — from 2013 to 2017, 21 African-Americans were killed by Columbus police. The youngest victim was 13 year-old Tyre King, who was killed in 2016.

Systemic racism within Columbus law enforcement has elicited an outcry from Black residents and a diverse community of allies. Protesters have called for a transparent investigation into Meade’s conduct, cutting funding to the Columbus Police Department, and an end to qualified immunity. They’ve also demanded that footage of the Dec. 4 shooting be released to the Goodson family and that the city cover funeral expenses. With the death of Hill on Dec. 22, the protests were amplified, with demands to restructure the Columbus Police Division and fire Quinlin. After Hill's death, members of the Columbus Freedom Fund hung a sign outside of City Hall that stated “Columbus is not safe for Black people.”

“Police [should] understand that what people are demanding are needs that [should] have been met a long time ago. History speaks for itself in terms of the Black community,” protester Harshita, who volunteered distributing Subway sandwiches in honor of Goodson’s last meal during protests on Dec. 11, told me. “People are asking for the privilege to access public services without having to fear something going wrong — we need to either abolish or reform [the police]. We cannot continue to use a system that is systematically used to oppress people [with] links to slavery and colonization.”

In support of the Goodson family, Goodson’s former middle school teacher Malissa Thomas-StClair spoke at the Ohio statehouse. In 2013, StClair’s 22-year-old son was murdered, after which the educator became a spokesperson against police violence in Columbus. Goodson stayed in contact with Thomas-StClair through Facebook over the years; their last exchange was on Nov. 6, when Goodson offered support for a former student of Thomas-StClair who wanted to become a truck driver.

“If someone made an action that was against the law, they need to be taken into custody, and they’re supposed to be not guilty until proven innocent. I look at white criminals over and over again on Facebook and they’re treated with sensitivity, even if they have weapons,” Thomas-StClair told me. “We cannot have any more Black men — who are innocent like Casey Goodson — continue to have bloodshed. A mission of mine as an educator is to continue to be a voice for my students who are alive, but more importantly those like Casey Goodson Jr. who have passed on.”

As emotions continue to run high in Columbus, the CPD has been silent about systemic oppression pertaining to the Black community. After two weeks of protests, Hill’s death threw fuel on the fire. He was killed by CPD officer Adam Coy, who was fired on Dec. 28 for unreasonable use of force. Residents have been patient with the police department for decades, but protesters now call for real justice.

“[Accountability] would require them first to understand [the police department’s] roots in white supremacy,” protester and educator Fevean Keflom told me. “Being in spaces where police officers have done community policing — they talk about diversity groups or police officers who are a part of task forces — but every time you ask them about their training, it never starts with the history of where policing stems from.”

Far too many times this year, a city has been left reeling because of the unjust, untimely, unnecessary death of a Black person. Columbus is the latest city to feel this turmoil. And even as residents call for increased transparency, the fight to end racial inequity is unceasing.