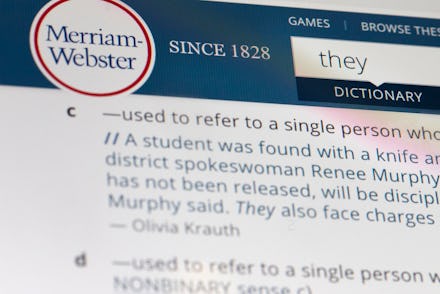

Merriam Webster announced its word of the year on Tuesday, and for the first time, the dictionary selected a pronoun, “They.” The decision, according to Merriam Webster, was made based on searching data. Emily Brewster, the senior editor at Merriam-Webster, released a statement explaining that the decision was made based on the amount of search data around the term.

“There's certainly some some people on Twitter, expressing disappointment in this choice of the word of the year because they think that it's some capitulation to social activists, and there are some people who are happy and excited that this word is Entering because it's a word that's important to them personally,” Brewster explained to Mic in a phone call. “And either case, you know, our responses just that this choice is completely data-driven. We looked at the frequency with which words were looked up at MerriamWebster.com.”

Merriam-Webster added the singular pronoun definition to the dictionary in September. At the time, Brewster explained to Mic, “since the dictionary has been online, we have been able to see what words people are actually interested in. That means the relationship between the dictionary and the public has been unidirectional, and now we can be part of the conversation.”

Brewster explained that the addition of the word “They” as a non-binary pronoun, and its selection as the word of the year was not meant to cater to or upset anyone. “We consider our job to be to tell the truth about words,” Brewster said. “And often what people look up in the dictionary says something about how words are being regarded by society at large. You know, we have millions and millions of people visiting Merriam webster.com all the time.”

Just like the word “Justice,” which was the word of the year in 2018, “They” captured some of the cultural moments in 2019. Sam Smith announced that they identified as non-binary — and within hours, the Associated Press already misgendered them. Merriam-Webster cited this event as one of the news events that drove search around the term.

“We take the job of monitoring the English language and the established words in the English language very seriously,” Brewster continued. “And by taking it seriously, I think we hope that people can use the dictionary as a tool to help them come to terms with language change, or to feel comfortable using words that are expanding in their in their use, or, or to just clarify their communication.”

And while Merriam-Webster’s addition of words and definition adds a certain amount of institutional formality, Brewster points out that even though the dictionary defines the English language, the dictionary doesn’t own it, or legitimize it.

“Everybody owns the language,” Brewster says. “A dictionary doesn't own the English language, all the speakers of English own the English language. They push it and make it do the work that they need it to do, to communicate, to get their ideas and their thoughts and their feelings out and to make themselves be heard and understood.”