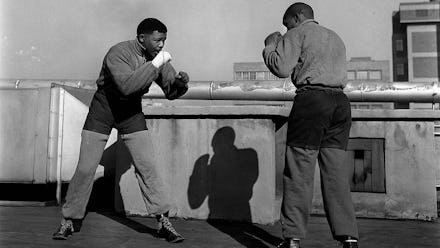

What Nelson Mandela Was Doing in His 20s

As we remember the long and inspirational life of South African president and political activist Nelson Mandela, we should keep in mind that the august leader who led the charge to end apartheid was once an ambitious young man with only his convictions to guide him, and no way of knowing the impact his work would eventually have on the world. Mandela’s story is that of an exceptional human being, but also the story of an idealistic young man who took setbacks in stride and always held close to his principles, even to his detriment.

The charming grandfatherly man who was released from prison in 1990 and won South Africa’s first multiracial election in 1994 began adulthood in Johannesburg as a college dropout who ran away from home. In 1939, Mandela started at student at the University of Fort Hare, the only institution of its kind that accepted black students, but despite his love of learning, he would not remain there for long. A year after enrolling, Mandela would be suspended for participating in a student council boycott of the school. When he returned home, Mandela’s understandably frustrated guardian, Chief Jongintaba Dalindyebo, responded by arranging a marriage for Mandela.

Though he was, and would always at heart be, a country boy, in late 1940 Mandela packed his bags and snuck away to the city of Johannesburg in order to avoid the union — and, inadvertently, to begin his long and illustrious political career.

Mandela arrived in the city (he described it as "a maze of glittering lights which seemed to stretch out endlessly in all directions") with scant belongings. According to an anecdote in the PBS documentary The Long Walk of Nelson Mandela, he only had one pair of worn pants at the time, which was particularly a source of embarrassment when it came to dating. He began working as a security guard at a mining company, but was let go when his employer discovered that he had run away from home. He then found work as a law clerk through ANC activist Walter Sisulu, who would become Mandela’s fellow prisoner and lifelong friend.

Despite a long commute, Mandela thrived at the left-leaning firm, and completed his undergraduate degree by correspondence. He pursued but failed to obtain a law degree through the University of Witwatersrand, where he was the only black student, but was able to pass the qualifying exam that would enable him to practice as an attorney. (Ever determined, Mandela never gave up on receiving his law degree; he studied in prison and graduated from the University of South Africa in 1988.) Even without a degree, Mandela went on to open a law firm that offered low-cost services for black clients as they sought justice in an abjectly unjust system.

In 1944, at the age of 26, Mandela helped found the ANC’s Youth League, through which he found his true calling. He also married his first wife, Evelyn Mase, who would soon give birth Mandela’s first child. Mandela became president of the Youth League in 1947, and used his stature to respond to the National Party’s implementation of apartheid laws in 1948, fearlessly organizing boycotts and strikes in the midst of raising a young family (his 9-month-old daughter would pass away that year) and sitting for legal exams. Mandela’s family life fell by the wayside as he became ever more dedicated to the cause of defeating apartheid (and also, in part, due to his history of womanizing). His convictions and dedication to the ANC cause would only become stronger as he entered his 30s, and began to be arrested and tried for his activism.

Mandela’s turbulent 20s point to the fact that even the most lionized and respected of world leaders face uncertainty and setbacks as young adults, as they struggle to balance idealism, education, work, and their personal lives. Like most young people, Mandela fought to forge his own path. However, his unwavering determination in the face of adversity should be a lesson for us all. Mandela’s strong beliefs and persistence were not only enough to see him through his struggles, but sufficient to bring down a deeply terrible, deadly, and racist regime, and to encourage the cause of equality in both South Africa and around the world.