Remember those brain-eating amoeba? Thanks to climate change, they're moving north

As the climate crisis continues to worsen, the list of its impacts continues to grow. The latest: A recent study conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that warming waters and temperatures are pushing brain-eating amoebas northward. The report, published Wednesday in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases, stated that while the rate of annual infections hasn't increased, the geographic location of the infections has steadily moved from the South toward more Midwestern states.

You may have heard of brain-eating amoebas before. Although they're rare, it feels like they hit the news every year, when unsuspecting swimmers fall victim to the deadly infections. This past September, a 13-year-old boy died from an amoeba after vacationing in Florida, and a 6-year-old boy died in Texas after playing in a city-operated "splash pad."

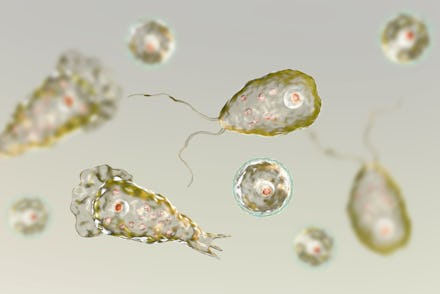

Formally known as Naegleria fowleri, the amoeba can be absolutely brutal for folks who enjoy a good swim. N. fowleri loves to lurk in warm freshwater, like lakes and rivers, and can infect a swimmer when the water goes up their nose. The amoeba follows the water up the nasal canal and enters the brain, causing an illness called primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM) — a disease that's almost always fatal. There are only four known survivors of PAM in the U.S., one of whom ended up with permanent brain damage.

Thankfully, you can't get an infection from drinking contaminated water; it only happens when water enters the nose. That's not much comfort for swimmers, though.

For the recently released study, CDC researchers studied four decades' worth of data related to N. fowleri infections in the U.S., spanning from 1978 to 2018. They selected 85 cases that fit their criteria — ones that stemmed from water infections and had location data — and noted them on a map. The scientists also took a look at the environment and weather at the time of infection.

Although most of the earlier N. fowleri infections occurred in southern states, recent infections have been documented as far north as Minnesota. Other states with notable cases included Indiana and Kansas. The research team also learned that each location experienced an average two weeks of higher-than-normal air temperatures leading up to the infections.

"It is possible that rising temperatures and consequent increases in recreational water use, such as swimming and water sports, could contribute to the changing epidemiology of PAM," the authors concluded. In other words, the increase of swimming-friendly temps caused by climate change are a win for brain-eating amoeba.

Unfortunately, we still don't have a consistent way to track the risk of PAM infections or calculate the number of amoeba in the water. "It is unknown why certain persons become infected with the amoeba while millions of others exposed to warm recreational fresh waters do not, including those who were swimming with people who became infected," the CDC website states.

It's one big reason why this study is important, particularly as the climate crisis continues to warm parts of the nation. By figuring out the amoeba's ideal living conditions, epidemiologists can better identify circumstances when outdoor swimming is riskiest and keep the number of infections low.