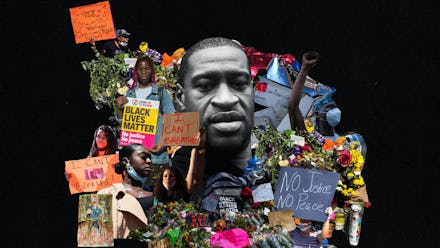

Here's how much has really changed since George Floyd was murdered

Tuesday, May 25, marks the one-year anniversary of George Floyd’s murder at the hands of the Minneapolis police. Over the past 12 months, his death has served as a rallying cry for countless racial and social justice movements not only in the United States, but around the world. Here, Mic explores how inequality and injustice were brought to the fore in the wake of his killing.

On May 25, 2020, former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin murdered 46-year-old George Floyd. A cell phone video of Chauvin — who is white — kneeling on the neck of Floyd — who was Black — helped to catalyze the summer’s protests demanding an end to state-sanctioned police violence against Black people.

Nationwide protests, largely led by Black and brown organizers, pushed the conversation of dismantling systemic anti-Black police violence into spaces that had previously refused it. Organizers and protesters called for elected officials to re-evaluate local police budgets, to divest funds from police departments into housing and education budgets, and to question if police actually make us safer.

Some cities decided to cut their police budgets, while others established departments of unarmed non-police social workers who could respond to mental health emergency calls. (It should be noted, however, that during the coronavirus pandemic cities cut many departmental budgets because of funding shortfalls, not just police budgets.) Yet police have continued to kill unarmed Black people: In fact, there has not been a decrease in police killings from 2020 to 2021, even with the increased national political attention on anti-Black police violence.

So in the past year, what has been accomplished? Mic has a list of proposals, from federal legislation to department-level changes to policing, that have come as a direct result of May 25, 2020.

Federal

George Floyd Justice in Policing Act 2020 — pending Senate vote

The George Floyd Justice in Policing Act of 2020 was passed in the House of Representatives and has yet to be called for a vote in the Senate. The legislation would tackle a number of police reform agenda items, including establishing a National Police Misconduct Registry and closing the “law enforcement consent loophole” that makes it legally permissible for a police officer to have sex with someone under arrest.

George Floyd Law Enforcement Trust and Integrity Act — pending House vote, Senate introduction

The legislation, introduced in the House by Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee (D-Texas), would require the Department of Justice to “take specified steps to address accreditation standards, management operations, and misconduct of law enforcement.” The legislation, which has yet to be called for a vote in the House or be introduced in the Senate, would require police departments to report data on traffic stops and use of deadly force, among others.

Ending Qualified Immunity Act — Pending House and Senate votes

Qualified immunity protects government officials — including police — from facing charges for constitutional violations, and has been used to shield officers from accountability for killing civilians. The Ending Qualified Immunity Act, which was reintroduced in March by Rep. Ayanna Pressley (D-Mass.) and Sen. Ed Markey (D-Mass.), would end the practice. It has yet to be called for a vote in either the House or the Senate.

Executive Order on Safe Policing for Safe Communities — In effect

In June 2020, then-President Donald Trump signed an executive order requiring “all state, local, and university law enforcement agencies be certified by independent credentialing agencies.” The order tied federal funding of police departments to the prohibition of chokeholds — except if a state allows the tactic. While the law seemed to achieve some broad-strokes priorities, like “independent credentialing” and more holistic training for officers, critics contend that by increasing funding to departments and empowering law enforcement to oversee itself, the order actually went against what reformers demand.

State

Colorado

In Colorado, Gov. Jared Polis (D) signed legislation last June that banned chokeholds (which seek to block airflow) and carotid holds (which seek to block blood flow). The legislation also removed the state’s qualified immunity statute and requires local police departments to report on use of force, among other reforms. Colorado police used a carotid hold on 23-year-old Elijah McClain, who died after being restrained by officers.

Connecticut

In June 2020, Gov. Ned Lamont (D) signed an executive order that banned chokeholds and other forms of neck restraints. The order also prevented the state’s Department of Emergency Services and Public Protection (DESPP) from purchasing military-grade weapons and tools.

Iowa

The Iowa state legislature passed a bill that banned most chokeholds and required officers to undergo annual de-escalation and anti-bias training. The new law also allowed the state’s attorney general to bring charges against police and prevented police officers from finding further employment in the state if they were fired for misconduct. It was signed by Gov. Kim Reynolds (R) in June 2020.

Massachusetts

Massachusetts passed legislation in December that included a number of changes to state policing, including the creation of a mandatory certification process for all officers, banning the use of chokeholds, and limiting no-knock warrants.

New Jersey

In June 2020, the state’s attorney general announced that police departments would no longer be authorized to use neck restraints like chokeholds or carotid neck holds. The attorney general did provide an exception in the new rule for use of force to allow for police to use a chokehold when they felt threatened.

New York

In June 2020, Gov. Andrew Cuomo (D) signed legislation that banned the use of chokeholds, empowered the state’s attorney general to prosecute police officers who kill unarmed civilians, repealed a law that previously allowed officers to conceal misconduct records, and prohibited racist and false 911 calls, such as the one Amy Cooper made in Central Park on May 25, 2020.

Local

Atlanta, Georgia

Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms (D) signed executive orders requiring officers to use non-lethal de-escalation tactics, with possibly lethal methods available only as a last resort. Among other changes, all police killings will be reported to and evaluated by a citizen review board.

Austin, Texas

Residents of Austin petitioned the city council to defund the police department by $150 million. The city council also banned police use of so-called “less lethal” weapons during protests, like rubber bullets and bean bag rounds, and created stricter guidelines for when police officers can shoot suspects.

Bay Area, California

A number of Bay Area cities took legislative action to address police and police budgets. San Francisco voted to remove $120 million from the police department’s budget over the course of two years. The funds will be reinvested to support the city’s Black residents via a guaranteed income program ($7 million), increased social work outreach ($6.6 million), and housing security support ($10 million), among others. In June 2020, San Francisco Mayor London Breed (D) announced that the city’s police would no longer respond to non-criminal calls.

In Oakland, the city council approved the creation of the Mobile Assistance Community Responders of Oakland program, which sends non-police with appropriate medical and mental health training to non-violent emergency calls. The school board also unanimously voted to remove police officers from its schools.

Berkeley followed suit by passing the Safety for All: George Floyd Community Safety Act, which included a 12% police budget cut. The city council also voted on changes to the police department’s policy regarding traffic stops, calling for an end to traffic stops as a result of “minor offenses” among other changes, per The Mercury News.

Houston, Texas

The mayor of Houston signed an executive order regarding de-escalation techniques, limiting use of force, and banning no-knock warrants.

Kansas City, Missouri

Per Missouri law, cities have to allocate 20% of the budget toward its police department. The mayor of Kansas City announced that the next budget cycle would not include funding over that 20% floor, saying instead that the city would redirect anything over 20% into a newly created Community Services and Prevention Fund. Local Fox affiliate Fox4KC reported that the mayor did not tell the police department its funding would be slashed before implementing the new budget.

Los Angeles, California

Organizing by People’s Budget LA, a project of the city’s Black Lives Matter hub, pushed the city council to divest $150 million from the police budget. The city also agreed to cut overtime hours for the department and to disband a number of costly specialized units.

Louisville, Kentucky

The Louisville City Council passed Breonna’s Law, which banned the use of no-knock warrants. The law also demands that police officers turn on their body cameras “five minutes before and after searches,” per ABC News.

Minneapolis, Minnesota

Minneapolis enacted a number of changes in the wake of Floyd’s murder. As a result of a temporary restraining order, the city banned chokeholds and other forms of neck restraints. The Minneapolis school board also ended its contract with the police department, which had accounted for $1.1 million annually of the district’s funds.

New Orleans, Louisiana

The New Orleans City Council voted to prohibit the use of tear gas in most police-related encounters, including protests.

New York City, New York

City council members approved a bill that will require the police department to report its use of surveillance technology. Known as the Public Oversight of Surveillance Technology bill, it will also require that the department set standards of use and that those standards be reviewed annually. The city council also passed legislation that criminalizes police use of neck restraints, requires that officers display their badges while on duty, and creates a “disciplinary matrix” which “gives a recommended range of penalties for each type of violation,” among other changes.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

City council members are expected to approve a citizens’ police oversight commission that would retain subpoena power in order to investigate police misconduct and violence. It will likely be approved when the next budget is voted on this year.

Portland, Oregon

In Portland, activists pushed the school board to end its contract with police.

Salt Lake City, Utah

Salt Lake City’s mayor signed an executive order detailing seven different police reforms. Included are changes to use of force policy, which now require police to use de-escalation strategies. Additionally, police are no longer allowed to use deadly force to prevent someone from harming themselves. (People suffering from mental health crises account for nearly half of all police killings.)

Seattle, Washington

Seattle, which created a police-free zone in its downtown area last summer, made a number of changes to policing tactics. In June 2020, the city council banned chokeholds and the use of tear gas to disperse crowds (which was often used against protesters), as well as banned police officers from covering their badge numbers.

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser (D) approved legislation to ban the use of neck restraints on individuals and devices like tear gas or stun grenades for the purpose of dispersing protesters.

Individual departments

This is not a comprehensive list, but rather a sampling of changes some police departments have enacted on their own:

Bellevue, Washington

The police department banned chokeholds in situations where an officer does not deem deadly force necessary. Chokeholds are still allowed for situations “when the officer’s life is in danger” per the Bellevue police chief.

Dallas, Texas

The police chief implemented policy changes within the department to require that an officer intervene when another officer uses excessive force.

Denver, Colorado

The Denver police department banned chokeholds and created a new policy requiring that an officer file a report if they “intentionally point their gun at someone,” per the Associated Press. Other changes include requiring the SWAT team to wear activated body cameras.

Davis, California

The police department banned chokeholds without exception and established an intervention policy that requires police to stop their peers from using excessive force.

New York City, New York

The department agreed to dismantle its “anti-crime” unit, which consisted of 600 plainclothes officers. According to The Intercept, plainclothes officers comprise just 6 percent of the NYPD yet are responsible for 31 percent of killings.

Phoenix, Arizona

The police department suspended the use of a carotid restraint in favor of a hold that doesn’t target someone’s neck.

San Diego, California

In June 2020, the police department banned the use of carotid holds without exception.